What’s it all about?

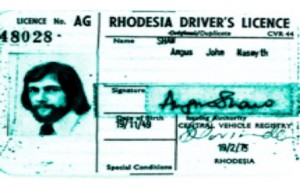

I have been a journalist and writer all my working life. We started out on typewriters, learned shorthand, fact checking, ethics, criminal law, constitutional law and the Bill of Rights and the laws of libel and slander. Since 1968 I have put tens of millions of words to paper or screen, and on air, so why stop now?

Hence this website. I have been retired at the age of 65, and given the state of the news media today it’s perhaps not such a bad thing. A journalist never retires, you might say. That’s right. But the old style reporter has been overtaken by time – the worldwide web, social media and the steady decline of traditional newspapers. Traditional media outlets are on ridiculously strict budgets, gone are the all expenses paid assignments and the old timers who have a different – some say old fashioned – way of doing things are the first to be sent out to the pastures of retirement during all the ruthless cost cutting that is going on.

This website aims to be entertaining and interesting. It won’t let some things pass unnoticed. Like this front page headline – a splash headline as it’s known in the trade – from the South African Sunday Times.

Above all, the site is meant to be thought provoking and fun. It’s certainly fun to put together. It goes without saying, it is also to plug my books and keep myself in the media marketplace. As I always say, journalism offers a rich and rewarding life, except financially.

I had always dreamt of being a newspaper editor. But in independent Africa it wasn’t to be, for the obvious reasons of my white settler ancestry. The site tries to be a one-man publication – I am the editor – as well as being a storeroom for writings, journalism, photos and audio and video clips, old and new, good and bad.

A final word on how I never became a newspaper editor in Africa. See Mutoko Madness, by Angus Shaw, Boundary Books, pages 154/155. I was an editor for one day. This was way before we got cellphones:

The editor went deep into the bush for a family funeral and asked me, back at Herald House now, to take the helm for the day. It was New Year’s Eve, and Shehu Shagari, the civilian president in Nigeria, was overthrown in a military coup. I splashed the coup story as the front page lead and put Mugabe’s New Year message as the anchor story on the bottom of Page 1.

Members of Robert Mugabe’s security detail would come down to the print works to collect the first edition; they had told me that he always wanted his paper by five in the morning, when he had finished his bedroom exercise regime of press-ups and other manoeuvres from a ‘stay fit’ training book. Evidently, he didn’t sleep more than five hours a night. This time he was livid that we had made Shagari the main story and I was summoned to his office later in the morning.

‘Oh, it’s you,’ he said. ‘Where is Musarurwa?’

‘At a funeral,’ said I.

‘Well, I won’t have you sacked this time, but try and find a reasonable understanding of the way we do things, of our protocol, and of our respect for our leaders,’ he said.

Willie Musarurwa got a dressing-down when he returned from the funeral in the bush. It had been my first and last day as editor of a newspaper in independent Africa.

‘I thought I could trust you to get it right. Didn’t I tell you to lead with Mugabe?’

In the shifting sands of the new order, Willie was fired long before I was. I lasted through two more fired editors before I was sacked too. In the early days, recalcitrant whites weren’t seen be as much of a threat as blacks who criticised from within. Mr Mugabe tolerated people like me and Ian Smith. He expected us to be not progressive enough and said he could have had Smith’s head on a silver platter after independence but that he and I were relics, we were dinosaurs, and he was honouring the letter of reconciliation. After all that had gone before, I didn’t much like the idea of being a pea in the same pod as Ian Smith.

With Lou Boccardi, then president of The AP at an awards ceremony in New York, 2002. The citation for the Gramling prize, rated a coveted honour in the US newspaper industry, spoke of “courageous reporting from Africa.” In my speech, I said I accepted the award on behalf of “all in Africa who don’t enjoy the press freedoms that Americans take for granted.”