Bringing out our dead …

An American Blackhawk over coastal Mogadishu.

It’s hard to shelter from the deluge of news from Sudan and Ukraine. So PTSD brings all this back, particularly in the dark dreams of night …

Death, danger and destruction have a prominent place in history, especially in Africa. We accept it as a given until we have to bring out our own dead.

In six of the twelve countries I have worked in over the past four decades I have reported on nine wars, some places have had two wars in that time – counted among the nine – and I covered endless political upheaval, civil unrest and tragedy. In Uganda, I saw at close quarters Tanzanian troops gun down Libyan conscripts as they came out of a banana grove with their hands up. I saw Idi Amin’s prisons thrown open, revealing the corpses of victims most hideously tortured.

In six of the twelve countries I have worked in over the past four decades I have reported on nine wars, some places have had two wars in that time – counted among the nine – and I covered endless political upheaval, civil unrest and tragedy. In Uganda, I saw at close quarters Tanzanian troops gun down Libyan conscripts as they came out of a banana grove with their hands up. I saw Idi Amin’s prisons thrown open, revealing the corpses of victims most hideously tortured.

Ethiopia’s war against Somalia fought in the Ogaden desert and fighting in Liberia, Sudan, Mozambique and Zimbabwe should have prepared me for Somalia No. 2 in 1993 during the failed mission of United Nations peacekeepers, Americans among them.

The luxury Al Aruba hotel built for the African Arab summit in 1975, soon to be destroyed in fighting.

In Mogadishu, my photographer and friend Hansi Krauss was one of four journalists killed when an enraged mob turned on us. I was one of four journalists who survived the mob attack. Hansi fell within a few feet from where I stood.

In Mogadishu, my photographer and friend Hansi Krauss was one of four journalists killed when an enraged mob turned on us. I was one of four journalists who survived the mob attack. Hansi fell within a few feet from where I stood.

Early one morning we had gone to a villa the Americans had attacked with helicopter gunships. They believed, perhaps wrongly, it was a warlord base. The Somalis claimed it was a community meeting and women and children had brought fruit and water for the menfolk. Fifty four civilians were killed in the earthshaking onslaught of missiles and machine guns that attracted angry crowds who got there just as we did.

Hansi, two other photographers and a TV crew were the first to jump out of the cars. AK fire started, the crowd erupted and rocks slammed against our cars from all sides. Hansi went down, bludgeoned with a rock and shot in the chest, his flak jacked ripped off in the frenzy as I followed. Our Somali bodyguard yelled to me, grabbed me and pulled me back into the car. He pushed me to the floor and began shooting his 9mil pistol out of his window.

Fully surrounded, my passenger window shattered and hands were tearing at my shirt. Spit from shrieks of hate sprayed over my face. Some tried to stand in the way, stall the car, overturn it and kill us too. Speeding away, the car’s bodywork thumped dully through the crowd. We got out of “the killing ground” and out of range of the all-too-familiar brisk rattle of AKs firing at us. The attackers then began firing into the air and screaming in triumph over the bodies of our dead.

For once, these four were our own dead, not the scores of the nameless, faceless dead in battle, skirmish and disorder we write about every day.

Sarajevo

Hansi had once told told me he hoped that by bringing images of suffering to world attention he threw light upon darkness and, in some way, lessened the excesses of war. He had been in Sarajevo at the height of the war in Bosnia.

I didn’t agree. Somalis put on a show for the cameras a few days earlier over the dismembered body of an American GI. There was a shoulder, still in remnants of a bloody camouflage shirt, kicked around like a football. Hatred, killings, tensions and antagonism among all the belligerents, Muslim Somalis and UN Christians, increased daily.

I collected up Hansi’s belongings from his room at our fortress hotel, a converted office building, the Al Sahafi – his toothbrush was still damp – and there was a novel open on the pillow of his unmade bed. It was Patriot Games by Tom Clancy, just begun and left open at page 14. I spoke to Hansi’s family on a satellite phone, we arranged for our four dead to be flown to Nairobi where their families would take over funeral arrangements.

We wrapped Hansi in a sheet from my bed and drove him to the American mortuary where I had to formally identify him, sign the death certificate and nod at a verse read from the Bible. We burnt my sheet, washed Hansi’s reeking blood out of the back of the car. I bought a body bag from the Americans. The zipper of the bodybag was drawn up, covering torn underpants, the paleness of his blood-streaked body and his open glazed and empty eyes.

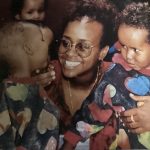

Hansi’s last published pictures taken the previous day at a Mogadishu orphanage were songs of hope, he had said

Hansi’s last published pictures taken the previous day at a Mogadishu orphanage were songs of hope, he had said

Death had suddenly become more than a paragraph in a newspaper.

The world over countless families do every single day and much, much more than what I did for Hansi Krauss, aged 30, a man with a name, a face, a personality, courage, kindness, a sense of humour, a sense of adventure, a man with loved-ones and ambitions and dreams, a man with a life.

We tend forget this until fatalities get so close and personal as they did that day.

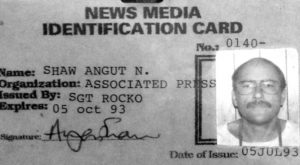

(A version of this article first appeared in Horizon magazine in Harare, Zimbabwe, in August 1993. I came home for ‘rest and recuperation’ – RnR – but soon was sent back to Somalia to follow the ultimate collapse of the disastrous U N peacekeeping mission whose Sgt. Rocko couldn’t even get my name right. My horrors in the Rwandan genocide were just a year later. )

(A version of this article first appeared in Horizon magazine in Harare, Zimbabwe, in August 1993. I came home for ‘rest and recuperation’ – RnR – but soon was sent back to Somalia to follow the ultimate collapse of the disastrous U N peacekeeping mission whose Sgt. Rocko couldn’t even get my name right. My horrors in the Rwandan genocide were just a year later. )

More weekend reading. Click on these two important links for the nature of conflict, why it’s always in the news and who goes to report on it and why. To some of us it’s inescapable, it’s our job. Go and find something other than that to earn a living, people say. There are classic war photos to be glanced at in both these links :

For the Americans, “Blackhawk Down” was the beginning of the end. Newly elected Bill Clinton pulled them out. Too many body bags going home and what was the point of it all.

Well said mate. I know how hard that was to write, and why you had to do it.