How to launder money

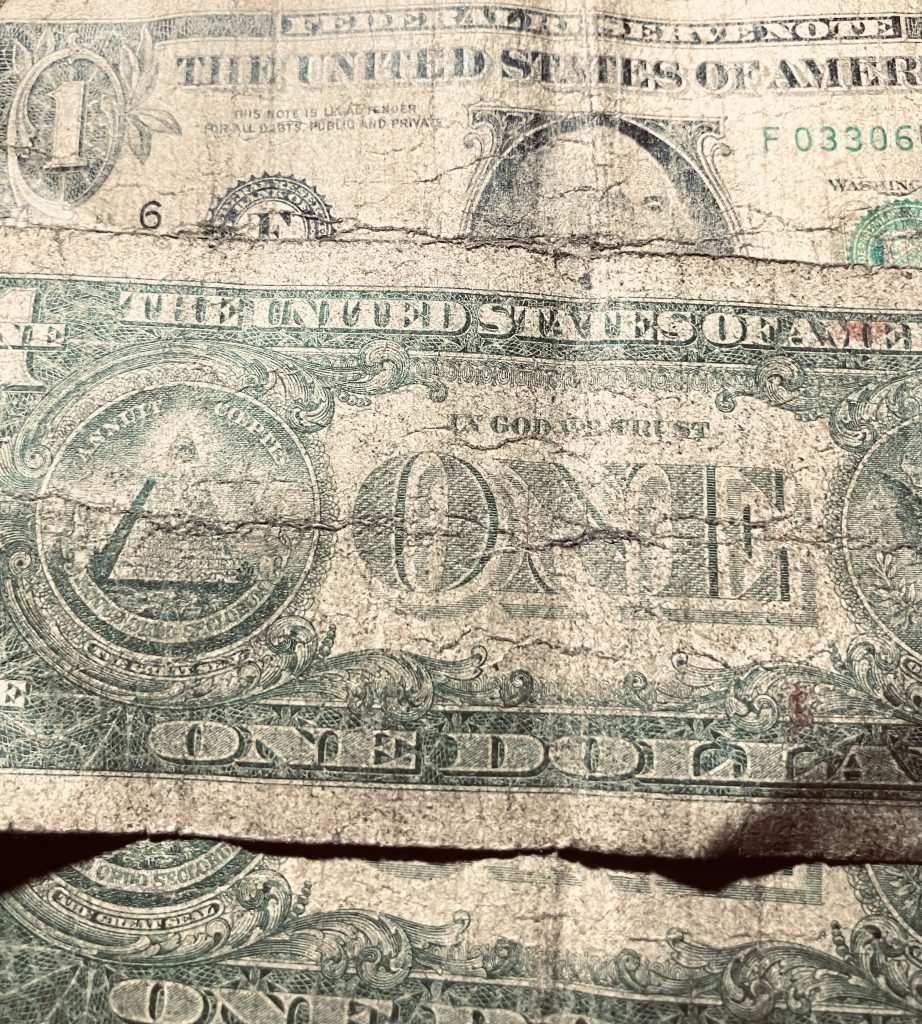

We tried washing grimy notes in gentle soap suds and warm water. Then a machine cycle took 45 minutes and the money came out cleaner than before.

We tried washing grimy notes in gentle soap suds and warm water. Then a machine cycle took 45 minutes and the money came out cleaner than before.

But it isn’t such an amusing story any longer.

New petrol stations, upmarket townhouses, glass-fronted office buildings and shopping malls are springing up everywhere. Ill-gotten cash buys land, fuel or construction materials and, hey presto, the money is laundered by new businesses that look legit.

This is how it works, explains the site foreman having a cigarette break between huge piles of bricks stacked out on the street near where I live. Old house with decent grounds is bought for US$ 350,000 cash, 12 townhouses/apartments fit into a secure, high-walled complex. They will sell for anything around US$ 250,000 each in cash, deduct US$ 700K for building materials, depending on the luxury required, and there’s a laundered profit of more than US$ 1 million. Get in while the going is good, the foreman tells me, because we are in a property boom that will inevitably crash sooner rather than later..

There’s an awful lot of money around but it is not to be found in ordinary pockets. For now, fewer restrictions apply to sending cash abroad from seemingly bona fide property sales and rents.

The powerful Financial Action Task Force says terror groups, drug cartels, arms dealers, political agitators and hackers need clean money more than ever before. FATF aims to control their inflows by blacklisting countries lacking accountability in their economies and that is precisely where Zimbabwe finds itself.

The powerful Financial Action Task Force says terror groups, drug cartels, arms dealers, political agitators and hackers need clean money more than ever before. FATF aims to control their inflows by blacklisting countries lacking accountability in their economies and that is precisely where Zimbabwe finds itself.

The blacklist means FATF tells reputable foreign banks to close any zw-linked accounts and most comply. And there are always other less compliant tax and banking havens out there.

Forty countries and the World Bank and IMF subscribe to FATF’s crusade. Unfortunately, many legitimate offshore accounts (including my own of 50 years standing) have been shut down. My bank did have the good grace to give me notice to find a different resting place for my meagre savings from a lifetime of roving journalism.

Forty countries and the World Bank and IMF subscribe to FATF’s crusade. Unfortunately, many legitimate offshore accounts (including my own of 50 years standing) have been shut down. My bank did have the good grace to give me notice to find a different resting place for my meagre savings from a lifetime of roving journalism.

In better days when I reported on that Zimbabwe-style money laundering we first tried washing-up liquid and warm water and then the washing machine cycle. Dry cleaning didn’t work well because the chemicals involved stained American bills.

In better days when I reported on that Zimbabwe-style money laundering we first tried washing-up liquid and warm water and then the washing machine cycle. Dry cleaning didn’t work well because the chemicals involved stained American bills.

Dirty notes are hidden in shoes, underwear and spare car tyres and smuggled across borders from cities and crime-ridden slums across the continent. The gentle hand-wash did little harm to the cotton-weave type of paper. For security reasons, the U.S. Federal Reserve has never officially divulged exactly what paper weave the bills are made of.

According to the Fed in conditions in America the $10 and $20 bills last about two years and the $5 lasts an average 16 months, slightly less than the $1 bill there.

Around here, damaged, filthy U.S. banknotes can remain in circulation at rural markets, bus parks and beer halls almost indefinitely – or at least until they finally disintegrate.

Around here, damaged, filthy U.S. banknotes can remain in circulation at rural markets, bus parks and beer halls almost indefinitely – or at least until they finally disintegrate.

One US $1 bill given in change bore the signature of Lawrence H. Summers whose three-year tenure as Secretary of the U.S. Treasury ended in 1999.

Bring out the rubber gloves, the disinfectant hand wipes.