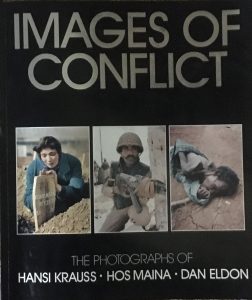

IMAGES OF CONFLICT

Horst Faas, veteran war photographer and twice Pulitzer price winner wrote this:

On Monday 12 July 1993, a mob murdered four men who were working as photo-journalists in Mogadishu, Somalia. The four were separated from a convoy of media cars as they tried to photogroph a United Nations helicopter assault and were attacked by angry Somalis. Those kiled were Hansi Krauss (30), an Associated Press photogropher from Germany, two Reuters photographers, Hos Maina (38), and Dan Eldon (22) and Reuters sound technician, Anthony Macharia (21).

Men and women working for Reuters and The Associated Press once again had fo mourn collegues who paid the ultimate price for reporting from the rim of a volcano of inhumanity, volence and tragedy.

Hansi Krauss became the sixteenth AP reporter or photographer to die by violence in the line of duty since 1938.

The death of Dan, Hos and Anthony increased Reuters Roll of Honour to ten names since the Vietnam War.

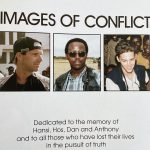

This book shows the dedication of our dead friends to the jounalistic task of reporting. Their commitment to a high standard of photographic work and the compassionate touch that shines through the usually grim subjects of their photography. The portfolios left behind, especially those by Dan Eldon and Hansi Krauss, are slim; both were just at the beginning of their careers.

Unlike fhe works of other great photographers who died by war and violence, their photographic testaments are incomplete. The pictures in this book are just an outline of the promise of greatness that the future may have held.

Unlike fhe works of other great photographers who died by war and violence, their photographic testaments are incomplete. The pictures in this book are just an outline of the promise of greatness that the future may have held.

Robert Capa, role model for many an aspiring news photographer, was 41 years old when he was killed by a landmine in Thal Binh, North Vietnam during the Indochina War in l954. He began his career and first won fame photographing the seeds of war in the early 1930s. He Iived through the hellfires of this century’s biggest wars. His portfolio spans 25 years of the world at war.

Hansi Krauss was only 30 when he died, barely three years after he started life as a big-time photo reporter at the Berlin Wall. His work was original, but in his photographs there are intimations of what John Steinbeck saw In Capa’s work: “the picture of the great heart and an overwhelming compassion.”

Larry Burrows, the dedicated and brave Life magazine photographer who carried into his war photography all the principles of compassion and excellence that characterised his pictures, was 44 years old when on 10 February 1971, his combat helicopter (with four other photographers aboard) was shot down over Laos. There were no survivors. His work shows the wide range of a man who was both a journalist and an artist. Compassionate war photography was only one part of his pre-eminent gift for composition, technical excellence, sense of beauty and strength of expression. Larry was a highly experienced photographer and the range of his subjects was endless. British born, Larry Burrows began his career, which was to span 29 years, in London as a dark room technician.

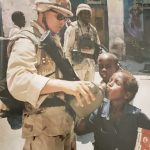

Dan Eldon’s photographs remind us of Larry Burrows. But his career lasted barely 29 months. His work shows an unusual directness. He did not dodge an issue and his photographs seem fo come directly from the heart. The work of this so very young photographer expresses something rare in today’s news photography – that there is not only doom ond gloom, but hope and even love in the most desperate human conditions.

Dan Eldon’s photographs remind us of Larry Burrows. But his career lasted barely 29 months. His work shows an unusual directness. He did not dodge an issue and his photographs seem fo come directly from the heart. The work of this so very young photographer expresses something rare in today’s news photography – that there is not only doom ond gloom, but hope and even love in the most desperate human conditions.

Hos Maina and Anthony Macharia did not have to travel far from home on their assignments. During their working lives famines and civil wars were on the doorstep of their native Kenya. Their work shows that they, too, felt responsible for making the world aware of their continent’s tragedies.

The photographers whose pictures are shown in this book were not war photographers. They were professional agency photographers who did not shy away from routine jobs. They had to manage a variety of assignments from fashion shows to catastrophes, from VIP visits to soccer garmes. They belonged to that special breed of reporter-photographer who are forever drawn to events that challenge perceptions of the world and society, events that make history. Such events usually produce víolent photographs: the turmoil of demonstrations, the brutality of war, the suffering and death of the innocent and the arrogonce of power. But they can also provide a record of the good in actions of those who believe they can help.

The photographers whose pictures are shown in this book were not war photographers. They were professional agency photographers who did not shy away from routine jobs. They had to manage a variety of assignments from fashion shows to catastrophes, from VIP visits to soccer garmes. They belonged to that special breed of reporter-photographer who are forever drawn to events that challenge perceptions of the world and society, events that make history. Such events usually produce víolent photographs: the turmoil of demonstrations, the brutality of war, the suffering and death of the innocent and the arrogonce of power. But they can also provide a record of the good in actions of those who believe they can help.

But these photographers are not satisfied when their assignments only show us yet another famine, another civil war, another crowd of refugees, more bloodied bodies. The task these photographers set themselves is beyond mere documentation.

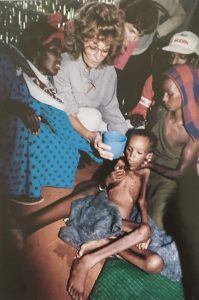

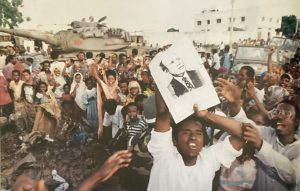

Sophia Loren in Mogadishu

They try to catch emotion, to peer into the hearts and minds of their subjects, so that we, the public, may understand the events even better. When one simple plcture says everything about the despair, the horror or the hope of people, and if such a photograph causes reaction or even compassion around the world, then it is photo-journalism at its most meaningful and satisfying. Some photographers may set out with a mission growing from a perfectly honest concen. They may want to prove that war is hell, or that mass starvation can dehumanise people. They not only report an event but become part of it. Reporting for a news agency, as did Hansi, Hos, Dan and Anthony, is different. Like artists, news photographers may strive to do a good job while remaining outside observers, but it is hard for them to remain objective because they become deeply serious about their assignments and involved in their subjects.

Their best pictures are not accidents or strokes of luck. They are usually the result of much thought, observatlon and patience, plus the courage required to go where a picture must be taken.

The victims of Mogadishu were not ordered to go there nor were they ‘soldiers of fortune’: they had the courage to ask for assignment to Somalia.

When the news of their deaths reached the closely knit fraternity of news reporters, one reaction was heard over and over again: ‘No job is worth dying for.’ No doubt our friends believed that too.

When the news of their deaths reached the closely knit fraternity of news reporters, one reaction was heard over and over again: ‘No job is worth dying for.’ No doubt our friends believed that too.

Any photographer who maintains that a good photograph is worth the risk of death, or worse, that he has no fear, either lies or is a danger to himself and his colleagues.

Many journalists who had to deal with similar uncontrollable situations in the past (and were lucky enough to survive) asked and analysed whether the deaths in Mogadishu could have been avolded.

Did the newsmen go one step too far? There is no indication that this particular incldent was more dangerous than many other events that Hansi, Hos, Dan and Anthony had covered. Newsmen and photographers that cover war and violence have to convince themselves that the death of a colleague was either caused by carelessness or that it was a tragic accident. They must convince themselves that it cannot happen to them. If a non-combatant observer, like a photographer, does not believe that, he or she cannot continue.

“There is no doubt in my mind that I, and I think most of my colleagues, would have done what they did, taken the same risk,” said one photographer who used to work in Somalia. They died because fellow human beings wanted to kill them. Once confronted by their murderers they had no chance.

Experience and instinct could not save them. It could have happened to any of us.

Sarajevo

A photographer who was working in Sarajevo when he heard about the deaths in Mogadishu was asked if he wanted to continue. He wrote to me saying “We all have our own reasons. Please respect those reasons and do not challenge us to justify our action. Whenever we decide to go into dangerous situations we must not believe that things will go wrong. We must be confident. That is why you must always respect anyone who says ‘No, l will not go.’ We must trust our instincts.”

On the day they died in Mogadishu, our four colleagues made a judgement that the importance of the story outweighed the risks to themselves. They were trying to tell us something that they believed we needed to know. We must not forget that, as we must not forget them and all the other men and women who have died in the line of their professional duty or for their beliefs.

Horst Faas, September 1993.

Mohamed Amin, renowned veteran Africa photojournalist wrote this:

Mohamed Amin, renowned veteran Africa photojournalist wrote this:

“May you live In our hearts for a thousand years

And may each year have fifty thousand days…”

Anthony Macharia was born on 5 May 1972 in the Kenyan village of Uthiru, just outside Nairobi.

He was raised by his grandparents, Stanley Macharia and Salome Wanjiru, while his parents were at work. He was educated at Uthiru nursery and primary schools. Anthony graduated to Kaniti Secondary School before jolning Pumwani Secondary School in Nairobl a year later. There his discipline and behaviour earned him the appointment of head prefect.

His ready smile and easy manners marked him out as a natural leader, and both at school and at home he was the focus of his contemporaries. His spiritual upbringing was the charge of the Anglican St. Peter’s Church, Uthiru, where he was baptized in 1978 and confirrned in 1982. At eighteen, his schooling ended and Anthony found work at Kenya Breweries. It was a job with few prospects. He was an impressive young man with an irresistible sense of humour and clearly deserved better. I had known his family for many years so, early in 1992, I Invited Anthony to join the staff of my publishing company as a picture-researcher. Despite the pressure, he displayed constant enthusiasm for his work and always had an eagle-eye for detail.

Such were his application and efforts that he transferred to the Reuters Television Africa Bureau in Nairobi after a few months to start training as a sound technician with a long-term view to him progressing to photographer or cameraman.

There he joined a close friend of his childhood, Patrick Muiruri, and became a formidable addition to the camera crew. Anthony was modest and unassurning, always cheerful and no load was too great for him, nor any task too menial. He was eager to help in every way and was clearly cut out for the job and Its challenges. Indeed, we marked him down for a great future in the intense competition of international television news.

Soundmen are the third member of any television camera crew, sharing the risk equally with correspondent and cameraman, but rarely with any public recognition. During the years many have died in action alongslde their camera colleagues tied by the umbilical cord of the recording equipment. Anthony had no concept of fear and his new responsibilities were characterised by an increasing degree of self-confidence and an intense enthusiasm for work.

His smiling face each morning brought a fresh sparkle to our Nairobi office. He was always willing to help his friends and colleagues in the office with any aspect of the work when he was not travelling on assignment. His first assignments were with Patrick in Kenya but he was soon travelling outside the country. He had first travelled to Somalia early in 1993.

Two months later he returned to Mogadishu fearless in the face of the aggressive mobs, always ready to joke and laugh with international news colleagues. Anthony was a tremendous colleague and a fine friend, a strength to lean on during dangerous hours. He will always be missed and his memory treasured.

Mohamed Amin, September 1993